A Generation at Risk: The Realities of Youth Unemployment in Europe and the UK

Despite ongoing economic recovery across much of Europe, youth unemployment remains alarmingly high in several regions, raising questions about the effectiveness of current labour market policies and education-to-work transitions.

Far from being a new challenge, youth unemployment has persisted across decades, shaped by both cyclical downturns and long-term structural issues such as skill mismatches, rigid labour markets, and geographic inequalities. The post-pandemic period and recent inflationary pressures have only magnified these divides, particularly between Northern and Southern Europe.

Recent data from Eurostat (2025) underscores the continuing concern.

-

The overall unemployment rate in the euro area rose slightly to 6.3% in May 2025 (from 6.2% in April), though still down from 6.4% in May 2024.

-

The broader EU unemployment rate held steady at 5.9%, slightly lower than 6.0% a year earlier.

-

An estimated 13.05 million people were unemployed across the EU in May 2025, with a 10.83 million residing in the euro area

But the picture becomes starker when focusing on young people (under 25):

• 2.864 million youths were unemployed in the EU in May 2025, of which 2.281 million were in the euro area.

• The youth unemployment rate stood at 14.8% in the EU and 14.4% in the euro area, both slightly up from the previous month.

• Compared with April 2025, youth unemployment increased by 9,000 in the EU and 13,000 in the euro area.

• Compared with May 2024, youth unemployment increased slightly by 3,000 in the EU but fell by 36,000 in the euro area.

These figures highlight a persistent divide: while overall unemployment is gradually improving, young people remain disproportionately affected, particularly in Southern Europe, where rates frequently exceed 20%. Beneath the modest year-on-year gains lie deep regional disparities in youth unemployment, both within the EU and in comparison, with the UK, underscoring the urgent need for more targeted and effective youth labour market policies.

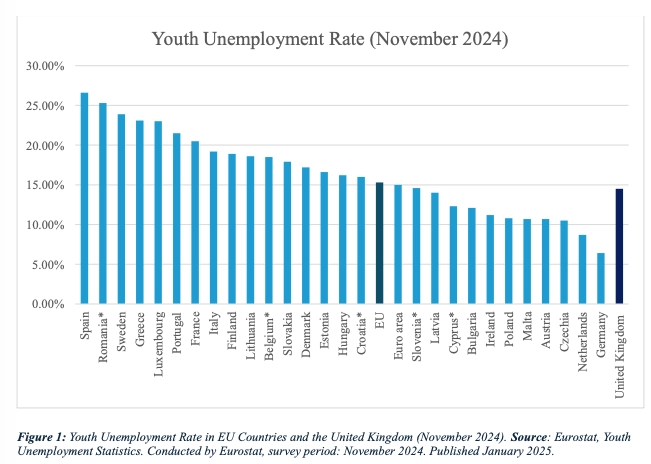

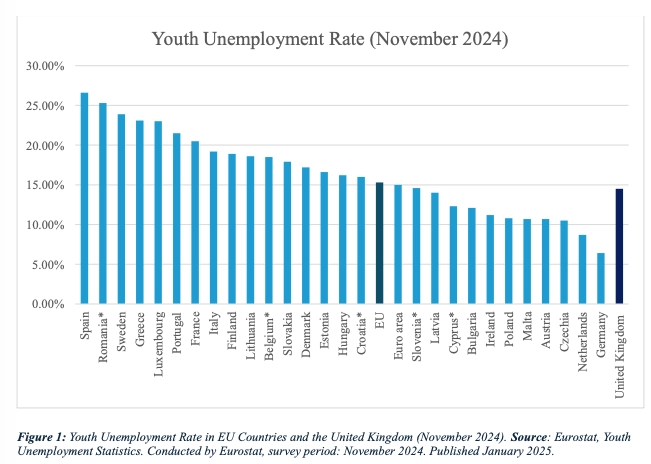

The figure below illustrates the seasonally adjusted youth unemployment rates across EU member states and the United Kingdom as of November 2024 (Eurostat, January 2025). Youth unemployment, defined as the share of the labour force aged 15 to 24 unable to find work, remains a significant concern across the region. Rates vary widely: Spain (26.6%) and Romania (25.3%) face the highest levels, reflecting persistent structural weaknesses, while Germany (6.4%) and the Netherlands (8.7%) report the lowest, underscoring the success of more robust training and employment systems.

The EU average sits at 15.3%, closely mirrored by the UK’s 14.5%, despite differing post-Brexit policy environments. This similarity suggests shared challenges, including graduate underemployment, skills mismatches, and regional disparities, issues that require both immediate attention and long-term structural reform.

This data illustrate that youth unemployment is not just cyclical, but deeply embedded in structural inequalities, with implications for long-term economic inclusion and productivity. Addressing these issues requires targeted interventions, ranging from education reform and vocational training to improved regional job access and employer engagement.

In this post, we explore the complex landscape of youth unemployment, focusing on four key areas:

• Regional and national disparities in youth unemployment rates across the EU

• A brief comparison between the United Kingdom and EU averages

• Insights from the data on how education, policy frameworks, and labour market access shape youth employment outcomes

• And how Stata can be used as a powerful tool for analysing these patterns through data visualisation and panel econometrics

A Historical Perspective: Youth Unemployment in Context

Youth unemployment in Europe has been a persistent challenge since the 1970s. Initially driven by demographic shifts, such as the entry of the baby-boomer generation into the labour market, it soon became clear that structural issues were at play. Even after the youth population declined, job prospects

for young people failed to rebound to earlier levels. This vulnerability became particularly evident during economic downturns. In 2007-2008, even as overall unemployment in the euro area fell to 7.5%, youth unemployment was already elevated at around 15%. The Great Recession exacerbated this disparity: from 2007 to 2013, youth unemployment in the euro area surged by 9 percentage points, double the increase seen in the overall jobless rate.

However, the impact varied sharply across countries. By 2013, youth unemployment exceeded 50% in Greece and Spain, tripled to 30% in Ireland, but fell in Germany, reflecting more resilient labour market institutions. As the euro area began its recovery, gaining over 6 million jobs across 17 consecutive quarters of growth, youth unemployment declined from 24% in 2013 to 19% in 2016. Nevertheless, it remained significantly above pre-crisis levels in many countries. Ireland, for instance, saw notable improvements, but other nations continued to face high rates of disengaged youth. Looking beyond unemployment rates, labour underutilisation remains a concern. In 2016, around 17% of 20–24-year-olds in the euro area were not in employment, education, or training (NEET). This share rose to 23% in Greece and 21% in Spain, highlighting broader social risks and long-term economic costs.

These patterns point to deep-seated issues in labour market structures across Europe. Youth unemployment remains not only pro-cyclical but also structurally embedded, requiring comprehensive, country-specific reforms.

Comparing the UK and EU: What's Happening in the UK Labour Market?

While youth unemployment remains a structural concern across Europe, the UK labour market presents its own evolving challenges, marked by recent data volatility and shifting participation trends.

In early 2024, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reintroduced Labour Force Survey (LFS) data after suspending its use due to reliability concerns in late 2023. Although the data has resumed, the ONS advises users to interpret the figures cautiously, particularly regarding short-term changes, as the estimates remain volatile and subject to revisions.

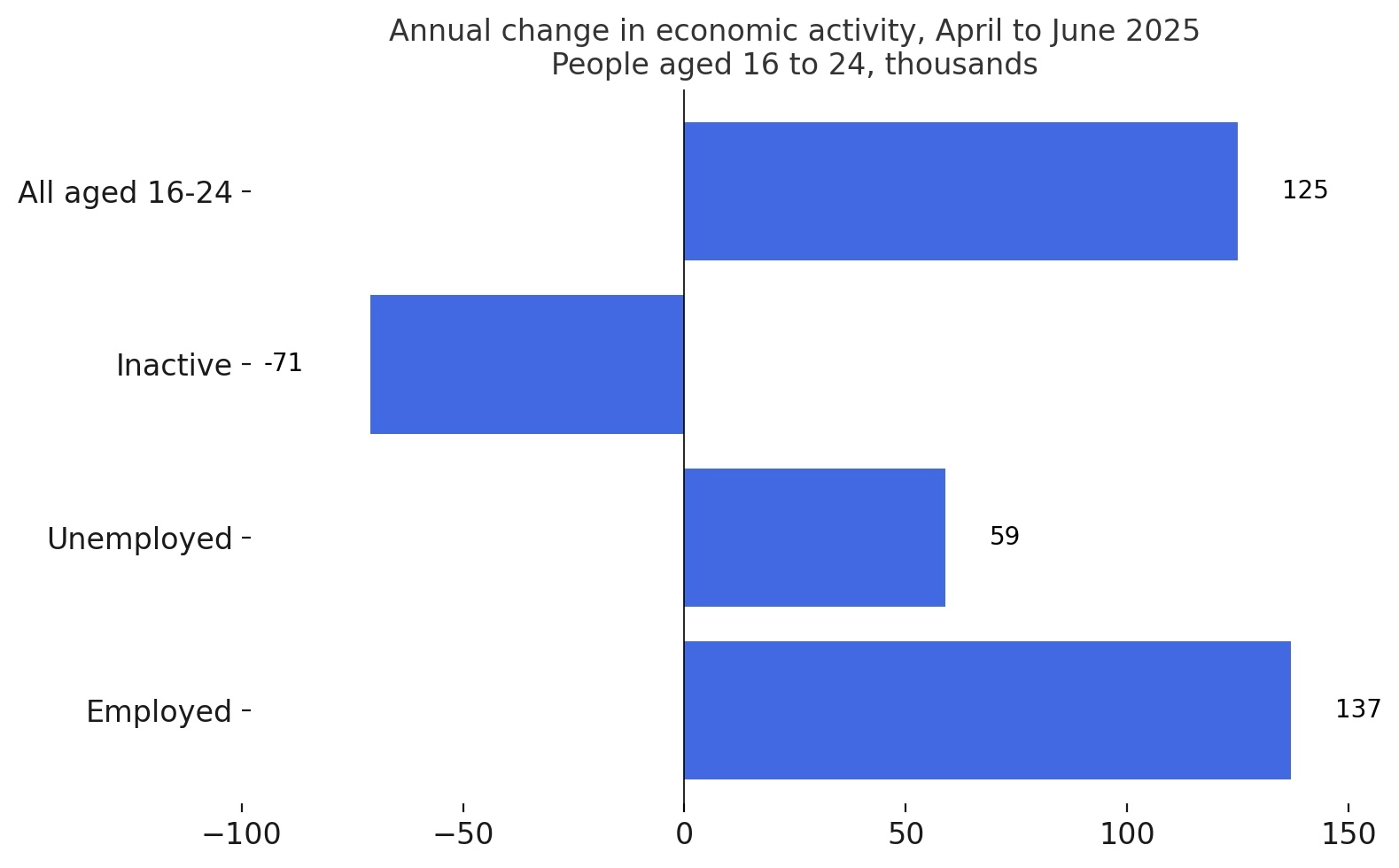

Nevertheless, the most recent figures for April–June 2025 offer insight into key developments among young people (aged 16 to 24) in the UK:

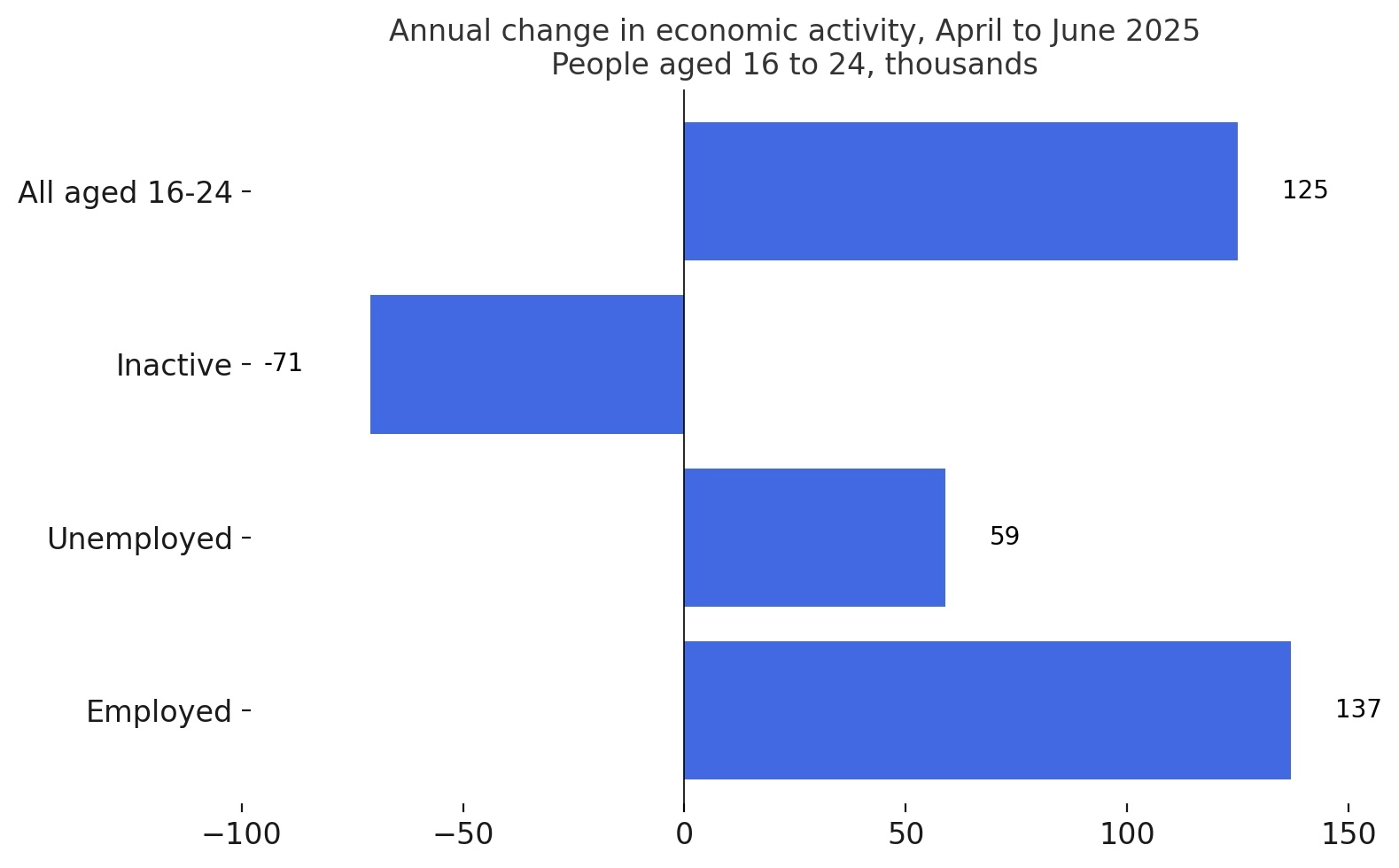

• Youth unemployment rose to 14.1%, up from 13.4% the previous year, with 634,000 young people unemployed, an increase of 59,000.

• Employment among young people also increased, with 3.85 million in work, up by 137,000 compared to the previous year. The youth employment rate reached 51.8%, improving from 50.8%.

• At the same time, economic inactivity among this age group declined. 2.94 million young people were economically inactive, down by 71,000. This brought the inactivity rate down to 39.6%, from 41.3%.

This data reflects a complex labour market picture: although more young people are entering employment, unemployment is also rising, likely due to an increase in labour market participation as fewer remain inactive. In other words, more young people are looking for work, but not all are finding it.

This contrast with the EU is particularly striking. While youth unemployment in the EU and euro area also hovers around 14–15%, UK participation and employment rates have shifted more notably in recent quarters, possibly driven by policy changes, post-pandemic labour reallocation, or education trends.

The Figure 2 below illustrates the annual change in economic activity among individuals aged 16 to 24 in the UK, covering the period April to June 2025 (House of Commons Library, 2025). It highlights an increase in both employment and unemployment, alongside a notable decline in economic inactivity, suggesting more young people are entering the labour market, though not all are securing jobs. Data from January to March 2025 shows that 923,000 young people (12.5% of those aged 16–24) were classified as NEET, not in employment, education, or training. This group includes both unemployed and economically inactive individuals, underscoring the broader challenge of youth disengagement from the labour market and education systems.

Figure 2: Annual change in Economic Activity in the UK from April to June of 2025. Source: ONS,A06 SA: Educational status and labour market status for people aged from 16 to 24.

What's Driving Youth Unemployment in the UK? Structural Barriers and Regional Disparities

Youth unemployment has long been a stubborn feature of the UK labour market, with rates that consistently exceed the overall unemployment rate, a trend mirrored across many advanced economies, including the United States and European Union. But what makes young people particularly vulnerable

to labour market exclusion?

A 2021 report from the House of Lords Youth Unemployment Committee (Skills for Every Young Person, 2021) underscored the urgency of the issue, citing a youth unemployment rate of 11.7% and a NEET rate exceeding 12.6%. Despite a growing economy, these figures reflect persistent structural problems in education, training, and access to work.

Several key factors contribute to this situation such as:

Conclusion

The analysis of youth unemployment across Europe and the United Kingdom reveals a multi-layered and enduring issue, one shaped by both cyclical economic downturns and deep-rooted structural weaknesses. While countries like Germany and the Netherlands maintain relatively low rates, others, including Spain, Romania, and Greece, continue to face alarmingly high youth joblessness. The United Kingdom, though no longer part of the EU, mirrors the EU average, pointing to shared challenges in navigating post-pandemic recovery, educational alignment, and labour market entry.

Addressing these challenges requires a dual policy approach. On the one hand, demand-side measures, including supportive fiscal and monetary policy, remain essential for stimulating job creation and economic stability, particularly during periods of weak growth or recession. Such measures have been critical in cushioning the effects of recent shocks and helping younger generations benefit from a recovering labour market.

On the other hand, the structural causes of youth unemployment demand targeted, long-term solutions. Persistent mismatches between skills and employer needs, regional disparities in opportunity, and barriers to effective school-to-work transitions must be met with investments in education systems, vocational training, and active labour market policies. Additionally, strengthening financial stability through improved regulation and macroprudential oversight plays a key role in preventing crises that disproportionately affect young workers.

From a methodological perspective, Stata provides a powerful platform to explore, visualise, and model youth unemployment trends across regions and time. Whether conducting cross-country comparisons using panel data, identifying structural shifts in labour market participation, or visualising regional disparities through choropleth maps and bar charts, Stata enables users to transform raw data into clear insights. Moreover, its built-in econometric tools, from time-series forecasting to policy evaluation models such as difference-in-differences or synthetic control, make it particularly well-suited for evidence-based policymaking. As labour market challenges evolve, using robust statistical tools like Stata is essential to inform effective, data-driven solutions.

Ultimately, youth unemployment is not just an economic indicator, it is a signal of whether young people are being given a fair chance to contribute, grow, and thrive. The data is clear: addressing this issue is not optional. It is essential to ensuring both inclusive economic growth and social cohesion across Europe and the UK.

Francisca Carvalho, Lancaster University

Francisca is a third-year PhD student in Economics at Lancaster University. Her research focuses on climate risk factors and their impact on portfolio returns. She also teaches mathematics, econometrics, macroeconomics and microeconomics, to undergraduate and postgraduate students.

Dolado, J. (2015). No country for young people? Youth labour market problems in Europe. CEPR Press.Retrieved from https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/no-country-young-people-youth-labour-market-problems-europe

• Economics Help. (n.d.). Reasons for youth unemployment. Retrieved August 16, 2025, from https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/517/economics/reasons-for-youth-unemployment/

• Eurostat. (2025, January). Youth unemployment rate in EU member states as of November 2024 (seasonally adjusted). Retrieved from Youth unemployment in the euro area

• Eurostat. (2025). Euro area unemployment at 6.3% – Euro indicators.

• Ghoshray, A., Ordóñez, J., & Sala, H. (2016). Euro, crisis and unemployment: Youth patterns, youth policies? Economic Modelling, 58, 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.05.017

• House of Commons Library. (2025). Youth unemployment statistics (Briefing Paper Number 5871). UK Parliament. Retrieved from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk

• House of Lords Youth Unemployment Committee. (2021). Skills for every young person (Report of Session 2021–22, HL Paper 98). London: House of Lords.

• Statista. (2025). Youth unemployment rate in Spain in November 2024. In Statista Research Department. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com